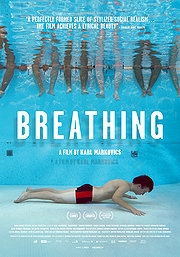

Breathing

For a film filled with calculated stillness and wide, mathematical shots, Breathing opens with a surprisingly jaunty walking bass refrain. Don’t be fooled – this is anything but an optimistic beginning. Nineteen year old Roman Kogler (Thomas Schubert) is an orphan, serving time in a juvenile detention centre for the last 5 years after accidentally killing a boy in a childhood brawl. His probation finally upon him, we meet him struggling to find – and more importantly, hold down – a job as a condition of his release. Options on the scant side, Kogler eventually settles for a job at municipal morgue in Vienna, where his daily routine consists of collecting and delivering the dead, either from the morgue to a funeral or from their place of death to an odd container situated at the back of a cemetery.

It’s during this placement that Kogler discovers the corpse of a woman who shares his family name – and despite his seeming emotional paralysis, his heart leaps. Though it soon becomes clear that this is not the body of the mother he never knew, his suddenly piqued interest in his long-lost family remains, and he cannot help but wonder what his roots actually are. But in refusing to accept help help from his counsellor – the only person actually on Roman’s side – and isolating himself from the rest of the teens in his detention centre, it becomes clear that Roman’s failure to connect with the living extends far further than too much over-time at the morgue…

Karl Marcovics is best known for his role as devious “Sally” Sorowitsch in the 2008 Best Foreign Oscar winner, The Counterfeiters, and Breathing is his first foray into direction. Marcovics’ directorial debut is shot almost like a documentary, not with the wobbling shots of an amateur crew, but with steady framing and religious employment of the photographic rule of thirds – the style is grounded and realistic. The sound design is similarly free of fancy; cold and metallic, punctuated with the slamming and clattering of the metal trays with which the mortuary crew transport their corpses. It all makes for satisfyingly unpretentious and viewing; stripped down dialogue and focus on story means that you cannot help but feel that no shot is being wasted.

Schubert is brilliant as the permanently adolescent Roman Kogler, but – perhaps suitably – it does take time to warm to both him and his character. From the outset he’s your archetypal brooding teenager; obtuse, stubborn and refusing to conform to either society or the etiquette of his detention centre. Marcovics’ direction constantly emphasises how ill-fitting Roman’s surroundings seems to be; a ample-bosomed woman on a holiday billboard at the station taunts him daily with her permanent technicolour smile, an advert for a life he’ll never be a part of. Fellow inmates sit and watch from the side of the swimming pool as Kogler doggedly swims his solitary lengths, the rest of them keen to muck around with a ball.

But this is not simply a film about isolation, and as the story progresses we begin to see chinks of light amid the sullen darkness. Roman’s tempestuous relationship with his co-worker, a momentary flirtation with a stranger in a train cabin, his growing determination to locate his birth-mother all hint at Roman’s desire to begin re-connecting with a world he was sure he had written off, a second attempt at living that comes so slowly and gradually that it’s difficult to pinpoint at all.

It is this thawing from cold to some sort of warmth that Breathing does so well; from the blue-tinted realism of the film to the highly sensitive sound design that picks up on every sigh and every footstep, it all adapts with Kogler’s emotional growth. The weirdly comic jazz bass that opened the film begins to be cut early in scenes, and is replaced by a far more ethereal, calming and contemplative soundtrack – almost as if Kogler is no longer seeing the outside world as a farcical construct that he’s not part of, but something that he’s starting to feel immersed in. Marcovics flirts with different genres, showing a brief flicker of blossoming romance, taunting us with a familial resolution, but doesn’t commit fully to any of them, apparently determined to stick to the staunch realism that made up the first half.

Ultimately, it’s Marcovics commitment to the mundane, to the anti-climactic and to the small truths of everyday living that really gives Breathing its heart. Proving that its often in highlighing the banalities of life that we are made thankful for existence in general, Breathing‘s real success is in reminding us that sometimes, simply deciding to live at all can be triumph enough.

By Oliver Baxter

Recent Comments