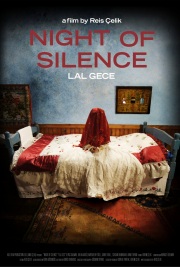

Night of Silence

In a tiny Turkish village, a middle aged man is welcomed back to his family after spending most of his life in prison. He is paraded through the streets amid the shouting of revellers, the barking of dogs, and the exhilarated firing of guns. He is led to the house in which he will live out his freedom.

A teenage girl is dressed in white and covered with a red veil. She is given advice from all sides, adorned with bracelets that come with blessings from her new extended family, and left alone in what will, from now, be her bedroom. Whatever her new husband does, she is told, she cannot leave. Even if he beats her, she is told, twice, she must stay. Until she dies.

The two have never seen each other’s faces, and now they are married.

The biggest complication of the story is the fact that the bride (Dilan Aksüt) is unable to articulate how afraid she is, or why she’s afraid, to her groom (Ilyas Salman). “I’m just scared,” she says, repeatedly, to his utter bafflement. Why should she be scared, after all, when he is not a bad man? This should be the comment the film is making, and maybe it is, but somehow it comes across as a flaw in the story, and a frustrating one. It’s an alienating thing, to watch a grown man find himself completely unable to think of any reason a fourteen year old girl might be afraid the night she finds herself irrevocably tied to a man three times her age. The bride (who, although it’s left unsaid, probably has very little idea of what husbands do with their wives) is left to avoid the point as best she can; dancing with her husband’s temper as he does his best to make her less afraid, while having no idea what she fears.

It’s an easy assumption to make that, in a culture in which child brides are still common, there must be little sexual honesty or openness. There is much in this situation that, due to the culture around them, the bride and groom dare not speak. But somehow that fact is left for the audience to assume; the dark undercurrent of the unspoken is never felt as palpably as it needs to be.

There is beauty here, and heart. Director Reis Çelik favours strong colours and overlong establishing shots that pick at the mind and demand attention. There is no music to undercut the tension, which serves to make the two seem very alone, and very separate from the audience. Aksüt is excellent; sweet and tremulous, and panicked, spinning away into elation when she’s delayed her doom by another few moments. Salman, too, is highly watchable; this isn’t a tyrannical colluder in an oppressive tradition, but a confused man, just beginning to realised his on weakness.

It just feels like there should be something more. The stakes should be higher, there should be a sense of danger, of claustrophobia. The climax (and I do mean the dramatic climax, obviously) leaves you feeling bemused and mildly interested, when you should be shellshocked.

Night of Silence is one of those films that leaves you feeling sad and horrified that this situation is a real one, one that happens to young girls in many countries, even today. But the film itself doesn’t grab you; the sadness you feel for these specific characters is light, and passes quickly. It’s a beautiful, slow depiction of a tragic custom, that never lets you feel the true pain of its story.

Recent Comments