Argo

Argo is a loose adaptation of the account of Tony Mendez, a CIA agent sent to Iran in 1979 to extract 6 staff members who escaped the storming of the US embassy by Iranian militants. Their brilliantly awful cover story was that they were a Canadian film crew location-scouting for Argo, a crappy Star Wars knock-off. The Iranian military are aware that 6 embassy staff are missing, and are slowing reconstructing photos of the wayward Americans. The faux-film crew’s fate hangs on a thread. Can they make it out of the country before they are outed?

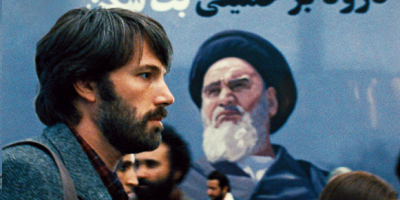

Despite the temptation to be completely jingoistic, Argo actually takes more of an apologetic tone when dealing with America-Iran relations in the late 70s. Admitting America’s support of the lavish Shah Pahlavi does much to create a non-judgmental and bipartisan atmosphere. This is lessened later on in the film, where every single Iranian appears hostile and dangerous, but considering the historical circumstances, this shift in tone feels more like an attempt to be reflect the fugitives’ anxiety rather than portraying an entire people as disagreeable.

After an awkward and clumsy exposition of the historical background of the time (it’s not great, but it’s necessary for us historically-ignorant folk) the film launches straight into the storming of the US embassy in Iran. It is phenomenal. The set design, the angry mob, the anxious embassy staff, every last detail feels exactly how it should. Even the lighting is tuned to perfection. There are also a few shots from inside the crowd taken with actual cameras from the late 70s that are thrown in. Nothing too much, just a quick shaky-cam glance cutting back to the modern day footage and you are hooked. This manic attention to detail remains for the rest of the film, which is the most impressive of all. It’s a shame that X-Men: First Class could not learn from the example of Argo about establishing the time period.

Argo is Ben Affleck‘s third foray into directing, and his second time directing and starring simultaneously. Although his directing impresses in Argo, his acting is a little peculiar. His character, Tony Mendez, is meant to be the protagonist, yet he feels oddly absent in every scene. This is especially awkward when the film attempts to develop Mendez’s character. If the intent was to humanise Tony by means of a couple of cheap references to his son and his broken family life, Argo missed the mark. This is especially relevant late in the film when Mendez feels less like a professional CIA operative and more like a piece of furniture that everyone has to tiptoe around.

Much more human than Ben Affleck are the supporting roles. Bryan Cranston, as a harried but competent CIA agent, is superb; he’s just on the right side of emotional, and his performance during the most tense part of the film is unparallelled. John Goodman and Alan Arkin play Mendez’s contacts in Hollywood who help him set up the fake film Argo to seem as convincing as possible. They nail their roles. Both cranky, jaded and loveable, they steal every scene away from Ben Affleck’s impression of a broken toaster. It is a shame that we see relatively little of Goodman or Arkin in the second half. The 6 embassy-escapees are all excellent too. Their uncertainty and fear remain palpable throughout the film, although they aren’t developed more than is necessary. Considering these actors appear to have been cast primarily on their ability to look like the original fugitives, their performances must be applauded, an unrecognisable Clea DuVall in particular.

The film takes takes on a markedly different tone in the time Mendez spends schmoozing his way though Hollywood, trying to set up the smokescreen of their fake film. It’s genial and lighthearted, pokes fun at the superficial nature of the industry, and is altogether very enjoyable. During this time, the film also maintains the tension of the events in Iran so that, although we are having fun in glitzy Hollywood, it still feels important and immediate to the plot. This tension truly ramps up in the final third of the film, when the plan to extract the Americans begins. It’s paced extremely well, and enhances the anxiety and suspicion by having every single non-white person surrounding the group be a potential threat. It does feel a little contrived sometimes, when every saving grace repeatedly happens just in time. However, the film has built up so much goodwill, and the tension levels are still so high, that you can forgive most of these niggling annoyances.

The problems that Argo has in dealing with the exposition at the start of the film one can forgive as a necessary evil. The painfully redundant text of “Based on a True Story” is jarring, but can be soon forgotten. Explaining exactly what happened to each and every character as the film is ending by text is decidedly inelegant. The credits of the film are presented lovingly, it seems like an odd choice not to have placed the conclusive text there.

It feels like nit-picking when one highlights these flaws. They do not detract from the overall enjoyment of Argo, which speaks volumes about the quality of the film. Most of Argo is spent developing anxiety: a slow zoom-in on a suspicious guard, or the monument in the CIA headquarters dedicated to deceased agents, does absolute wonders for this prevalent atmosphere. What is fantastic about Argo is that you are utterly rewarded for every single moment you spent biting you nails and clenching your sphincter. Audiences have already responded by making Argo a financial success, and it is getting an excellent reception from critics too. Do yourself a favour and find out why.

Recent Comments